Continuing with my series on Illinois Born major league players we find four from Olney, Illinois which is the home of the White Squirrel. Be sure to check that information out at the bottom of the article.

Illinois Born- OLNEY

Glenn Brummer

Glenn Edward Brummer (born November 23, 1954, in Olney, Illinois) is a former Major League Baseball catcher.

Signed by the St. Louis Cardinals as an amateur free agent in 1974, Brummer made his Major League Baseball debut with the St. Louis Cardinals on May 25, 1981, and appeared in his final major league game on October 6, 1985.

He played in 178 games with 347 at bats and collected 8 hits and 27 runs batted in for a .251 batting average. He had four career stolen bases but no more remembered than on August 22, 1982 he stole home with two outs in the bottom of the 12th inning to give the Cardinals a 5-4 win over the Giants.

Brummer was a member of the St. Louis Cardinals team that defeated the Milwaukee Brewers in the 1982 World Series.

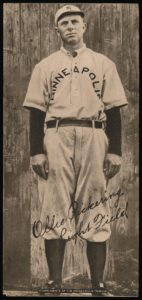

Ollie Pickering

Oliver Daniel Pickering (April 9, 1870 – January 20, 1952), was a professional baseball player and is noted as the first batter in American League history while playing for the Cleveland Blues in 1901. (NOTE: The 1901 season was the first season that the American League (AL) was classified as a “major league”) He went on that season to hit .309 and scored 102 runs for Cleveland. He played outfielder, primarily in center field, in the Major Leagues from 1896 to 1908. He would play for the Philadelphia Athletics, Louisville Colonels, Cleveland Spiders, Cleveland Indians, Washington Senators, and St. Louis Browns. Upon his retirement from playing the game, he became an umpire and later retired in Vincennes, Indiana.

Oliver Daniel Pickering (April 9, 1870 – January 20, 1952), was a professional baseball player and is noted as the first batter in American League history while playing for the Cleveland Blues in 1901. (NOTE: The 1901 season was the first season that the American League (AL) was classified as a “major league”) He went on that season to hit .309 and scored 102 runs for Cleveland. He played outfielder, primarily in center field, in the Major Leagues from 1896 to 1908. He would play for the Philadelphia Athletics, Louisville Colonels, Cleveland Spiders, Cleveland Indians, Washington Senators, and St. Louis Browns. Upon his retirement from playing the game, he became an umpire and later retired in Vincennes, Indiana.

The term “Texas Leaguer” is often attributed to the debut of Ollie Pickering, either in the majors or the Texas League, who came to bat and proceeded to run off a string of seven straight bloop hits leading fans and writers to say, “Well, there goes Pickering with another one of those “Texas Leaguers”.

A Texas Leaguer (or Texas League single) is a weakly hit fly ball that drops in for a single between an infielder and an outfielder. These are now more commonly referred to as flares, bloopers or “bloop single.” Most colorfully called a ‘gork shot’.

Dummy Murphy

Herbert Courtland “Dummy” Murphy (December 18, 1886 – August 10, 1962) was a shortstop in Major League Baseball. He played for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1914.

Herbert Courtland “Dummy” Murphy (December 18, 1886 – August 10, 1962) was a shortstop in Major League Baseball. He played for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1914.

Murphy started his professional baseball career in 1912. The following season, with the Thomasville Hornets of the Empire State League, he batted .338 and was drafted by the Phillies in September. He started 1914 as a major league regular. However, he batted just .154 in nine games and made eight errors in the field. He was released in May and went to the Jersey City Skeeters, where he batted .235 the rest of the season.

Murphy spent the next few years in the minor leagues, mostly in the Pacific Coast League. In 1920, he was a player-manager for the South Atlantic League’s Charlotte Hornets. He retired soon afterwards.

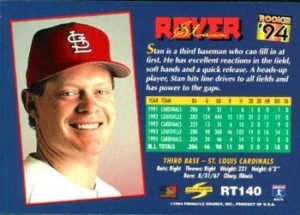

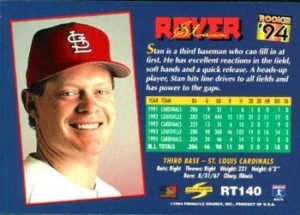

Stan Royer

Stanley Dean Royer was born August 31, 1967 in Olney, Illinois and attended Charleston High School in Charleston Illinois. He was drafted by the Atlanta Braves coming out of high school but chose to attend Eastern Illinois University. and recieved ab economics degree, In 1988, he was draft by the Oakland Athletics. He was traded in 1991 along with Felix Jose and a minor league player to the Cardinals for Willie McGee.

Stanley Dean Royer was born August 31, 1967 in Olney, Illinois and attended Charleston High School in Charleston Illinois. He was drafted by the Atlanta Braves coming out of high school but chose to attend Eastern Illinois University. and recieved ab economics degree, In 1988, he was draft by the Oakland Athletics. He was traded in 1991 along with Felix Jose and a minor league player to the Cardinals for Willie McGee.

He played first base and third base for St. Louis from 1991 through 1994. In a four season career, Royer was a .250 hitter (41-for-164) with 21 RBI in 89 games, including four home runs, 10 doubles, and 14 runs scored. He also played in the Oakland, St. Louis and Boston minor league systems from 1988–1994, hitting .270 with 72 home runs and 417 RBI in 707 games.

Royer is President of Claris Advisors, an investment advising and wealth management firm based in St. Louis.

Where is Olney, Illinois?

WIKIPEDIA ENTRY:

Olney is a city in Richland County, Illinois, United States. The population was 8,631 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Richland County.

According to the 2010 census, Olney has a total area of 6.664 square miles (17.26 km2), of which 6.66 square miles (17.25 km2) (or 99.94%) is land and 0.004 square miles (0.01 km2) (or 0.06%) is water.

As of the census of 2000, there were 8,631 people, 3,755 households, and 2,301 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,498.4 people per square mile.

White Squirrels

Olney is known for its population of white squirrels. There are two hypotheses about how there came to be white squirrels in Olney.

The first is that in 1902 William Stroup was out hunting and shot a gray female squirrel. The shot knocked the two babies out of a nest, and he brought them home to his children. They were later sold to Jasper Banks, who put them on display in front of his saloon.

The second is that George W. Ridgely and John Robinson captured a cream colored squirrel and then raised several litters of them before bringing a pair to Olney in 1902. Mr. Ridgely sold the pair to Jasper C. Banks for $5 each. Mr. Banks made a green box for his albinos and displayed them in his saloon window.

In 1910, the Illinois legislature passed a law prohibiting the confinement of wildlife, and they were released into the woods.

In 1925, the city passed a law that disallowed dogs from running at large. In 1943, the squirrel population reached its peak at 1000, but now the population holds steady at around 200.

In the mid-1970s, John Stencel, instructor at Olney Central College, received a small grant from the Illinois Academy of Science to study the white squirrels.

A squirrel count is held each fall. Both white and gray squirrels are counted in addition to cats. The number of squirrels has dropped causing concern. When the white squirrels dip below 100, they are concerned about genetic drift, or changes in allele (gene) frequency, which may reduce genetic variation and therefore speed up the extinction of a small population.

In 1997, the Olney City Council amended its ordinance which disallowed dogs from running at large to include cats. The 1997 squirrel count realized a decrease in cats. They are hopeful this will have a positive effect on the white squirrel population.

White squirrels have the right-of-way on all public streets, sidewalks, and thoroughfares in Olney, and there is a $750 fine for running one over. The police department’s badge even has a picture of a white squirrel on it. The white squirrel has proved to be an enduring symbol of Olnean pride, and stands as Olney’s most defining feature.

The population of white squirrels makes Illinois the only state to have populations of white as well as black squirrels, the latter residing in the Quad Cities area.