Pete Browning (1861-1905) – Namesake for Louisville Slugger

In my never ending quest to find baseball research, I have encountered many characters of the game which I am sharing with you.

Pete Browning 1861-1905

A genuine pre-modern national star, one of the major league game’s pioneers, and one of the sport’s most enduring and intriguing figures, Louis Rogers “Pete” Browning was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on June 17, 1861, at 13th and Jefferson on the city’s west side.

A lifelong resident of Louisville, Pete Browning was the youngest of eight children born to Kentucky natives Samuel Browning (1814-1874) and Mary Jane Sheppard Browning (1826-1911). They were married in Jefferson County, of which Louisville is the county seat, the day after Valentine’s Day in 1849. The family numbered, in addition to Pete, three sons and four daughters: Charles L., Henry D., Samuel L. Jr., Blanche N., Fannie E., Florence and Ida May.

In October of 1874, when Browning was 13, his father died at age 59 from injuries sustained during a cyclone. A prosperous merchant, Browning’s father had for years run a grocery store at the corner of 15th and Jefferson Streets in Louisville, not too far from the family’s residence. Browning’s mother, with whom the confirmed bachelor lived all his life, lasted substantially longer. She died April 6, 1911, at age 84 of old age at her home, 1427 West Jefferson Street, on the near west side of the city, having lived there for more than a half-century.

A skilled marbles player and name figure skater, Browning was a talented baseball player from the start. He made his first imprint on July 28, 1877, when he pitched a 4-0 win over the National League Louisville Grays. The young righthander’s strikeout victims that day included slugging outfielder George Hall and ace pitcher Jimmy Devlin — both participants in that season’s National League pennant-fixing scandal, which eventually cost the city its major-league team and resulted in the lifetime ban of five Louisville players

Browning’s reputation progressively increased during the next four years, spent principally with the city’s nationally known semipro club, the Louisville Eclipse.

Louisville went major league again in 1882, this time as a charter member of the fledgling American Association, the National league’s first great rival. His skills honed to a fine edge, Browning ran away with the American Association’s inaugural batting race, posting a .378 average. Thirty-six points better than that of his nearest rival, Cincinnati’s Hick Carpenter, it was also the best average in the majors, topping Dan Brouthers’ National League top mark by ten points.

During the course of 13 major league seasons, from 1882 through 1894, the bulk of that with Louisville in first the American Association and later the National League, Browning compiled a .341 lifetime batting average. Tied for eighth place on the all-time list with Cooperstown enshrinees Wee Willie Keeler and Bill Terry, the .341 mark ranks today as the fourth-best among the game’s right-handed batsmen. Only Hall of Famers Rogers Hornsby (.358), Ed Delahanty (.346) and Harry Heilmann (.342) have ever done better work from that side of the plate.

The work included one .400 season, and a trio of batting titles in two separate leagues. The latter makes Browning one of three 19th-century players to have won batting titles in two different leagues. Ross Barnes and Dan Brouthers are the others.

An instant major league star, Browning had a virulent drinking problem which didn’t take much longer to reach major league proportions itself, making its public bow in an August 13, 1882, contest against the Athletics. Despite the Louisville Courier-Journal’s story the following day over Browning’s drunken state, the team did not release its star, nor did it tighten the reins at all on him. Regardless of Browning’s heavy drinking, the club wasn’t going to release its homegrown, sensational rookie star who was on his way to a batting title and who had brought major-league baseball back to Louisville with a flourish.

Deaf and illiterate, the six-foot, 180-pound Browning was eccentric as well. He refused to slide; played defense standing on one leg to prevent anyone running into him; stared into the sun to improve his “lamps” (eyes); treasured his “active” bats because of the hits they still contained; was constantly on the prowl for the next, new “magical” stick with hits in it; reportedly favored bats that were 37 inches in length and 48 ounces in weight; maintained a warehouse of “retired” bats in his home — all of them named, many after Biblical figures; kept his batting statistics on his shirt cuffs; and when traveling over the circuit, frequently alighted from trains and introduced himself as the champion batter of the American Association.

Unlike many major-leaguers, Browning cut a swath through the sophomore jinx in 1883, batting .338 and finishing second to Pittsburgh’ s Ed Swartwood for league honors.

On May 12 the following season, while the team was on the road, Browning underwent major surgery for the first time for mastoiditis, an inflammation of the mastoid process. Located behind the ears and connected to the temporal bones that run along both sides of the head, the mastoid process are two honeycomb-like areas that occasionally aid the ear by acting as a surplus receiving area for violent sound vibrations that the ear cannot handle by itself, such as a sudden, nearby explosion.

For nearly his entire life, Browning was plagued by mastoidal problems. The impact of this malady is significant. It robbed Browning of his hearing. Because he could not hear, he refused to go to school out of frustration and embarrassment; the lack of schooling made him a virtual illiterate. The resulting sense of isolation, coupled with the savage physical discomfort attendant to the condition, fueled his uncontrollable drinking. It also prompted his commitment to an insane asylum, and was a major factor in his early death –both the product of a brain infection. In short, the mastoiditis was responsible for all his personal and professional problems.

However, the results of the 1884 surgery were unmistakable. Freed from mastoidal pain for the time being, Browning was highly productive that season, finishing third in the league with a .336 average.

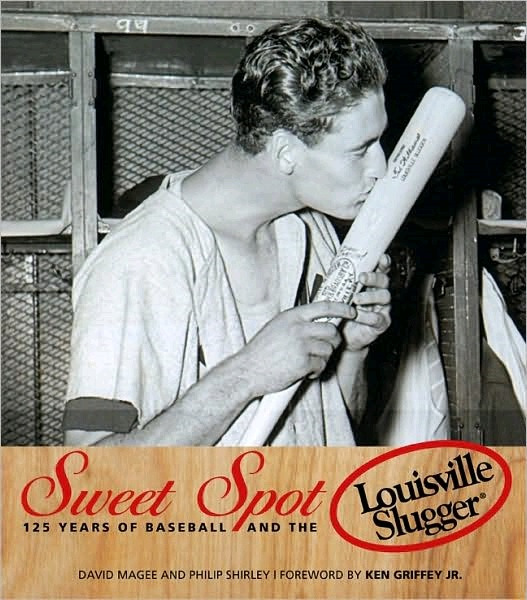

Far and away, however, Browning’s 1884 season is best-remembered for the famed Louisville Slugger bat incident. In the spring of that year, so the story goes, John Andrew “Bud” Hillerich custom-made a bat for Browning, who was in a slump. “The Gladiator” then went out and got three hits the next day, and, as they say, the rest is history. The incident forged modern batmaking, birthing two American icons — the Louisville Slugger bat and its equally renowned manufacturer, Hillerich & Bradsby.

In recent years, this story has come under inspection because no reference to it exists in either Browning’s obituaries or in that season’s baseball coverage. There are several other versions, also suspect, involving Gus Weyhing and Arlie Latham. Unquestionably, however, Browning is the namesake of the Louisville Slugger bat, and that is more than enough to sustain the longstanding historical link between the two. (At least three years before the name “Louisville Slugger” was registered as a trademark, Browning was referred to as the “Louisville Slugger” in the sub-headline of a June 17, 1891, Louisville Post article.)

Switched permanently to the outfield in 1885, Browning improved his 1884 average by 26 points, notching his second American Association batting title with a .362 mark.

In 1886, Browning narrowly lost the American Association batting title to Guy Hecker, the only pitcher ever to win a batting crown. Also the only pitcher ever to win a batting title and a pitching Triple Crown, Hecker held off Browning .341 to .340 (.3411078 to .3404710) as the race went down to the final day of the season. Hecker’s work also included a 26-23 mound slate.

Browning’s 1886 season also included hitting for the cycle for the first time against the New York Metropolitans on August 8, and being the victim of an unassisted pickoff play by Dave Foutz. Today, it remains the only documented case of a hurler picking off a runner unassisted without the benefit of a rundown.

There have been some two dozen legitimate .400 campaigns in baseball history, and Browning had one of them in 1887, hitting a career-best .402. It produced only a runner-up finish, however, as St. Louis’ Tip O’Neill hit .435. In 1888, Browning came up with a .313 average. The one-season drop in average was a direct consequence of baseball restoring the three-strikes-and-out rule, plus rescinding its one-season experiment (1887) in which walks were counted as hits.

Spiraling downward, Browning batted a career-low .259 in 1889. His average was a reflection of the doomed season as the Louisvilles finished in the cellar with a 27-111 record and a .196 winning percentage, 661/2 games back of the league champion Brooklyn Bridegrooms.

Along the way, they posted a streak of 26 consecutive losses, still the all-time major-league record; suffered the humiliating takeover of the team by the league, which was followed by the sale of the club; endured arbitrary fines and pay dockings by capricious owner Mordecai Davidson; survived a close call with the lethal Johnstown, Pa., flood; and engaged in a brief players’ strike, the first ever in major-league history, the participants including Browning.

Six players took part in the strike over Davidson’s refusal to forgive what the Louisville Courier-Journal called “heavy fines” he had imposed on two teammates. “Three amateur players were called into requisition,” the newspaper reported, to make up for the strikers. Louisville, without the six players withholding their labor, lost 4-2 on the road to Baltimore in a rain-shortened five-inning game, the 20th loss in the skein; the scheduled nightcap was washed out.

Oddly enough, Browning picked up his second career cycle game on June 7, during the middle of the losing streak. However, his season ended abruptly on August 11 when he was suspended the remainder of the campaign (a career-high two months) for drunkenness.

Jumping to the Cleveland Infants of the new Players League in 1890, Browning took the only batting title of that circuit with a .3732 average that just barely nipped Davey Orr’s .3728 work. But the season wasn’t just all hitting.

As a major-leaguer, Browning gained the nickname of “The Gladiator” for his ongoing battles with the fourth estate and his pathological alcoholism, best phrased by another memorable quote: “I can’t hit the ball until I hit the bottle!”

The moniker also was a reference to his battles with fly balls. However, recent research indicates that Browning’s fielding deficiencies, at the very least, deserve re-examination for several reasons: the crude equipment of the times, the typical fielding averages of his era, and the fact that Browning played three up-the-middle positions on the defensive spectrum: shortstop, second base and center field.

Moreover, the newspapers of his day published numerous accounts of his defensive prowess, those accounts running the entire length of his active major-league career. One of the best examples is an item that ran in the June 6, 1890, issue of the Cleveland Plain Dealer: “The one act of the afternoon which stands out like a wart on a man’s nose was a catch by Col. Browning (an embellishment; he was never in the military) in the fifth inning. Mr. [Hugh] Duffy, a distinguished townsman with whom it is a genuine pleasure to deal, tripped to the bat with his teeth set so hard that his jaw bones stuck out like handles on an Etruscan vase. He reached for the first ball which Mr. [Jersey] Bakely was good enough to land over the rubber.

“The sound that followed was the same as when the slats fall down in an old-fashioned bed. The ball mounted towards the town of Jefferson until it was lost to sight. It came into view again in a few moments in the extreme left field, and then it was observed that Mr. Browning was only a few rods away.

“He rattled his lengthy legs towards his heart’s desire as long as possible, and then jumped in a northwesterly direction, turning four times in the air and stretching one arm for the ball in a manner of a boy after his second piece of pie.

“He got it.

“Then applause went up from the grandstand like an insane man experimenting with a French horn. Pete had to doff his cap a dozen times.”

The 1891 season marked Browning’s third different league in as many seasons, and his first in the National League. Splitting the season between the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Cincinnati Reds, Browning batted .317 overall. The work included bunting into a triple play in early May. His season ended prematurely in early September after Kid Gleason hit him.

(For the record, this hit-by-pitch incident is indirectly related to one of three longstanding and persistent historical or statistical errors about Browning. All have been recently corrected by documentation, and here is how the record should read. Browning was first hit by a pitch early in his career, in July of 1883, not in May of 1890 as reported by at least one newspaper. Secondly, Browning’s correct number of cycle games was two, not three — the current major-league record. Finally, Browning did not die in an insane asylum.)

By 1892, major-league baseball found itself with only one league, the Players League having folded after the 1890 campaign and the American Association closing shop following the 1891 season. Back in his home city, Browning hit .247 in 21 games for Louisville before being released in mid-May. Once again, he caught on quickly with Cincinnati, batting .303 for them in 81 games and ending the season at .292.

The next year, Browning signed a contract with Louisville in late May and delivered on both sides of the diamond, playing sterling defense and batting .355 in just 57 games. Inexplicably, however, he was released in early August and played no more that year.

Browning’s major-league career came to a close on Sunday, September 30, 1894, in the finale of a closing-day doubleheader in his native Louisville. Playing right field for Brooklyn, The Gladiator singled twice in two official at-bats, walked once and scored once.

Officially, the final stop came in 1896 when Browning played his last recorded season of organized baseball at any level, batting .333 in 26 games with Columbus of the Western League.

The late 1890s found Browning working as a cigar salesman. He had owned a bar at 13th and Market Streets in Louisville, but that venture failed. Later, Browning turned to caring for his mother, and during baseball season, Browning was seen frequently at local baseball games. As in previous years, Browning was always well-received by the attendant crowds.

Browning’s comfortable retirement came to an abrupt end, however. On June 7, 1905, Browning was produced in the criminal division of Jefferson County Circuit Court, where he was declared a lunatic and ordered to the Fourth Kentucky Lunatic Asylum at nearby Lakeland.

After some improvement, Browning was removed from Lakeland by one of his sisters on June 21, 1905. A month later, he was admitted to old City Hospital (later renamed General Hospital and now called University Hospital), where he underwent surgery for ear trouble and a tumor of the breast. Following several stints in and out of the hospital, Browning died there on Sunday afternoon, September 10, 1905, at 2:15. Survivors included his mother; two sisters, Florence and Fannie; and two brothers, Henry and Charles (the father of famed film director Tod Browning, a protégé of the legendary D.W. Griffith).

Though the official cause of death was asthenia (a general weakening of the body), Browning’s medical problems no doubt included brain damage sustained by both the crudely treated mastoid condition and his longstanding defense against that malady – heavy drinking; cirrhosis of the liver, a product of his lifelong alcoholism; cancer; and most likely paresis, the third and final stage of syphilis.

Incurable even today, paresis is characterized by a total mental breakdown and is fully consistent with the times and Browning’s profession; his unstable mental condition toward the end of his life; and his personal habits, which included a longstanding fondness for prostitutes (newspapers on occasion referred to him thusly: “Pietro Gladiator Redlight Distillery Browning”).

Funeral services were held the following afternoon, September 12, at 2:30 at the home of Browning’s mother. From there, Browning was taken to Cave Hill Cemetery, the final resting place for many of Louisville’s major league ballplayers, as well numerous nationally prominent local and state figures.

His pallbearers included John Dyler, his first manager, and former teammate John Reccius, the latter a childhood friend and member of a noted Louisville baseball family that also included brothers Philip and William.

On September 10, 1984, as part of the centennial anniversary of the Hillerich & Bradsby Company, the company joined with the city of Louisville to honor Browning with a new grave marker that correctly spelled his name and fully detailed his lifetime baseball achievements.

A perennial candidate for Cooperstown via the Veterans Committee, Pete Browning made his most recent appearance on that committee’s 2003 Hall of Fame preliminary ballot.