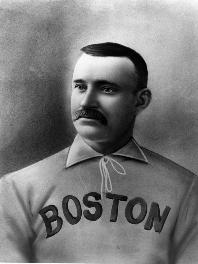

The 1908 Cubs Got into the World Series in Backhanded Way

Just a note about the last time the Cubs won a World Series. Seems a bit backhanded The 1908 pennant races in both the AL and NL were among the most exciting ever witnessed. The conclusion of the National League season, in particular, involved a bizarre chain of events, often referred to as the…