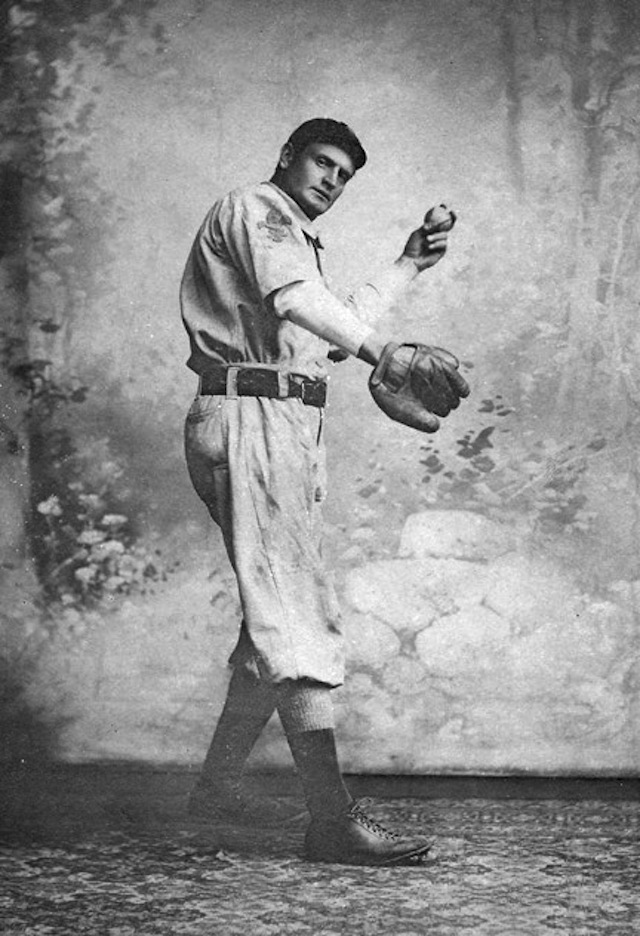

George Edward “Rube” Waddell – Eccentric and Strange Pitcher

There are many characters of the baseball world and Rube Waddell was certainly one of them. To add to his legacy, he was born on Friday the 13th and died on April Fools day It was all the stuff between there that made Waddell a character. At 6’1″ and almost 2oo lbs., he was a…