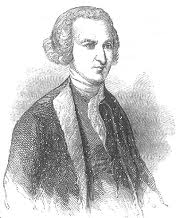

Candy Cummings 1848-1924 – The Man that Invented the Curveball

Continuing with the old time baseball players:

Candy Cummings 1848-1924

Candy Cummings, at first glance, appears to be one of the least qualified pitchers in the Baseball Hall of Fame. His major league won-lost record is usually listed as 21-22, because most career totals begin with the formation of the National League in 1876. Cummings earned his stardom in amateur play during the late 1860s and in the National Association, precursor to the National League, in the early 1870s. He enjoyed great success, but threw his last major league pitch when he was only 28 years old. However, Cummings, despite his short career, was one of the most influential pitchers in baseball history. He was selected for Cooperstown immortality because he, according to most baseball historians, was the man who invented the curveball.

William Arthur Cummings, called Arthur by his family and friends, was born in Ware, Massachusetts, on October 17, 1848. He was the second child of William and Mary Cummings, who moved to Brooklyn, New York, when Arthur was two years old. The family grew to include 12 children and appears to have been well off, because Arthur’s parents sent him to a boarding school in Fulton, New York, in his teenage years.

Cummings was an enthusiastic baseball player, and an outing with some friends in 1863, when he was 14 years old, gave Arthur the idea that changed the course of his life. He and a group of boys amused themselves at a Brooklyn beach one day by throwing clamshells into the ocean. The flat, circular shells could be easily made to curve in the air, and the boys managed to create wide arcs of flight before the shells splashed into the water. “We became interested in the mechanics of it and experimented for an hour or more,” recalled Arthur in his later years. “All of a sudden, it came to me that it would be a good joke on the boys if I could make a baseball curve the same way.” This seemingly passing thought started Cummings on a quest that took much of his time and energy for the next four years.

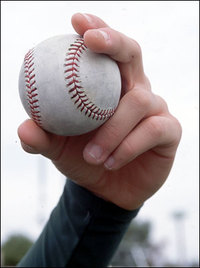

Throwing underhanded with his arm perpendicular to the ground, as stipulated by the rules at the time, Arthur practiced diligently and experimented with different grips and releases in an effort to find the secret of the curveball. In so doing, he made himself into an outstanding young pitcher in spite of his physical limitations. He grew to be about five feet and nine inches tall as an adult, but he never weighed more than 120 pounds at any time in his life. Even in that era, nearly a century and a half ago, he was small for an athlete. He also had small hands, usually a severe handicap for a pitcher. Arthur excelled on the mound anyway, perhaps due to the practice he gained from his pursuit of the elusive curveball.

In 1865, after Arthur graduated from the Fulton school, he joined the Star Junior amateur team of Brooklyn and posted an incredible 37-2 record. Later that year he was invited to join the Brooklyn Excelsior Club, one of the best amateur nines in the New York area. He soon became the team’s leading pitcher, and was so dominant that people started calling him “Candy,” a Civil War-era superlative meaning the best of anything.

In 1867, after four years of frustration, he found success with the curveball for the first time. He discovered that he could make the ball curve in the air when he released it by rolling it off the second finger of his hand, accompanied by a violent twisting of the wrist. Though it appears that Jim Creighton, a New York amateur pitcher, threw a ball with a quick jerk of the wrist in 1861 and 1862, Cummings was the one who combined it with the rolling motion from the fingers to maximize the amount of spin imparted on the ball.

Candy Cummings demonstrated his breakthrough in a game against Harvard College. “I began to watch the flight of the ball through the air and distinctly saw it curve,” wrote Cummings many years later. “A surge of joy flooded over me that I shall never forget. I felt like shouting out that I had made a ball curve. I wanted to tell everybody; it was too good to keep to myself.” All day long, Harvard batters flailed helplessly at the new pitch. The secret of the curveball was his, and for several years afterward Cummings was the only pitcher in the nation to claim mastery over the pitch.

The curveball made the 120-pound Cummings the most dominant pitcher in the country. He threw a pitch that none of the batters had ever seen or practiced against, and only when other pitchers learned to throw the curveball would batters learn how to hit it. Any pitcher who sought to copy Candy Cummings would need months, if not years, of steady practice of the type that Cummings had already accumulated. This gave Cummings a gigantic head start upon his competitors and made for an advantage that perhaps no other pitcher has ever enjoyed in the history of the game.

The varsity nine of the Brooklyn Stars signed Candy as their featured pitcher in 1868. The Stars billed themselves as the “championship team of the United States and Canada,” and with Cummings on the mound they were able to make good on that boast for the next four seasons. One source states that from 1869 to 1871, Cummings posted records of 16-6, 17-9, and 17-13 in top-level amateur play, and won many more in exhibitions against other outstanding ballclubs. In 1871, influential baseball writer Henry Chadwick named Candy Cummings the outstanding player in the United States, the closest thing at that time to a Most Valuable Player award.

The National Association began play in 1871 as the nation’s first professional circuit. Cummings remained with the Stars that season, but his skills were in such demand that he was besieged with offers. He signed contracts with three different Association clubs before the 1872 season started, but in mid-February the Association awarded Cummings to the New York Mutuals and made the pitcher a professional for the first time. Cummings pitched every inning for the Mutuals that year, posting a 33-20 record and helping the New York team to a fourth-place finish. He led the Association in games, complete games, and innings pitched. Candy struck out only 14 men all year, but strikeouts were exceedingly rare then, and he led the league in that category as well.

For the next several years Candy Cummings pursued increasingly generous financial offers with different teams in the National Association. In 1873 he signed with Baltimore, where he shared the pitching chores with Asa Brainard. Candy posted a 28-14 record as Baltimore finished a strong third. The 1874 campaign found the 25-year-old veteran in Philadelphia playing for the Pearls, and once again pitching every inning of every game. He posted a 28-26 record with a mediocre ballclub, but made national headlines on June 15, 1874, when he struck out six Chicago White Stockings in a row.

By the 1874 season, other pitchers began to make up ground on Cummings by developing curveballs of their own. Bobby Mathews, Cummings’ successor on the Mutuals, began throwing the pitch after learning it from Cummings. Alphonse Martin of the Troy Haymakers also threw a curve at about this time, though Martin later claimed that he had thrown it in amateur play in 1866, a year before Cummings. The controversy over the origin of the tricky pitch had already begun, with several rivals challenging Candy Cummings’ claim to preeminence in newspaper articles across the nation. Cummings, proud of his discovery, was keenly protective of his status as the inventor of the curveball, and for the rest of his life he zealously defended his claim against all doubters.

In 1875 Cummings landed on his fifth team in five years, the Hartford Dark Blues. The 1875 season was longer than previous campaigns, so the Hartford club divided the pitching load between Cummings and 19-year-old Tommy Bond, who played right field for the first eight weeks of the campaign while learning the curveball from Cummings. Bond mastered the pitch by mid-season, and by July he and Cummings provided an effective one-two punch for the Dark Blues. Hartford finished in second place as Cummings went 35-12 and pitched seven shutouts. Bond posted a 19-16 log and batted .273 as an outfielder.

Hartford joined the new National League in 1876. Cummings, for the first time in six years, stayed with his previous team and returned to the Dark Blues, but at the age of 27 he began to slow down. Tommy Bond pitched so well early in the season that he became Hartford’s main starting pitcher, pushing one of baseball’s most celebrated stars to the sidelines. Candy pitched 24 games in 1876 with a 16-8 record, while Bond went 31-13 in 45 games as Hartford finished third in the new league. On September 9, 1876, in the first scheduled doubleheader in National League history, Cummings pitched two complete-game victories over Cincinnati.

Candy declined to sign a National League contract that winter, instead joining the Live Oaks of Lynn, Massachusetts, in the new International Association. That winter, Cummings attended the convention that created the new player-controlled league, and the other delegates elected him as the first president of the circuit. However, Cummings did not stay long with the Live Oaks. He left the team in late June and signed with the Cincinnati Red Stockings of the National League, though he remained president of the International Association for the balance of the season. In Cincinnati, with a worn-out arm and a weak team behind him, Cummings won only five of the 19 games he pitched.

At the age of 28, Candy Cummings came to the end of the line. Other pitchers had learned to throw the curveball, and by 1877 batters had figured out how to hit it. Cummings, with his slender frame and small hands, no longer threw a curve well enough to fool the batters, and his arm was sore from ten years of top-level amateur and professional play. He pitched briefly in the International Association in 1878, but soon dropped back to the amateur and semipro ranks. Later that year he returned to his hometown of Ware, Massachusetts, where he learned the painting and wallpapering trade. He played ball sporadically until 1884, when he moved to Athol, Massachusetts, and opened his own paint and wallpaper company, which he operated for more than 30 years. He and his wife, the former Mary Augusta Roberts, whom he married in 1870, raised five children.

For the next several decades, Cummings passionately defended his status as the inventor of the curveball. He wrote dozens of articles and letters to editors defending his claim and refuting those, such as former Chicago White Stockings pitcher Fred Goldsmith and others, who claimed authorship of the pitch. His efforts paid off; by the early 1900s, such influential baseball men as Albert G. Spalding, player-turned-writer Tim Murnane, and Sporting News founder Alfred H. Spink had thrown their support to Cummings as the creator of the curve. By 1908, when Cummings wrote an article for Baseball Magazine titled “How I Pitched the First Curve,” his reputation was secure. Today, most baseball historians credit Cummings as the first man to make a ball curve in flight and also as the first to use the pitch successfully under competitive conditions.

Cummings retired from his paint and wallpaper business in the late 1910s, and in 1920 the widowed 72-year-old moved to Toledo, Ohio, to live with his son Arthur. William Arthur Cummings died in Toledo on May 16, 1924, and was buried in the Aspen Grove Cemetery in Ware, Massachusetts. Fifteen years later, on May 2, 1939, a special committee elected Candy Cummings and five other 19th century players to the Hall of Fame.