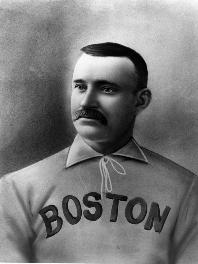

Ross Barnes (1850-1915) Hit First NL Home Run

Ross Barnes (1850-1915) Roscoe Conkling Barnes (May 8, 1850 in Mount Morris, New York – February 5, 1915 in Chicago, Illinois) was one of the stars of baseball’s National Association (1871-1875) and the early National League (1876-1881, playing second base and shortstop. He played for the dominant Boston Red Stockings teams of the early…