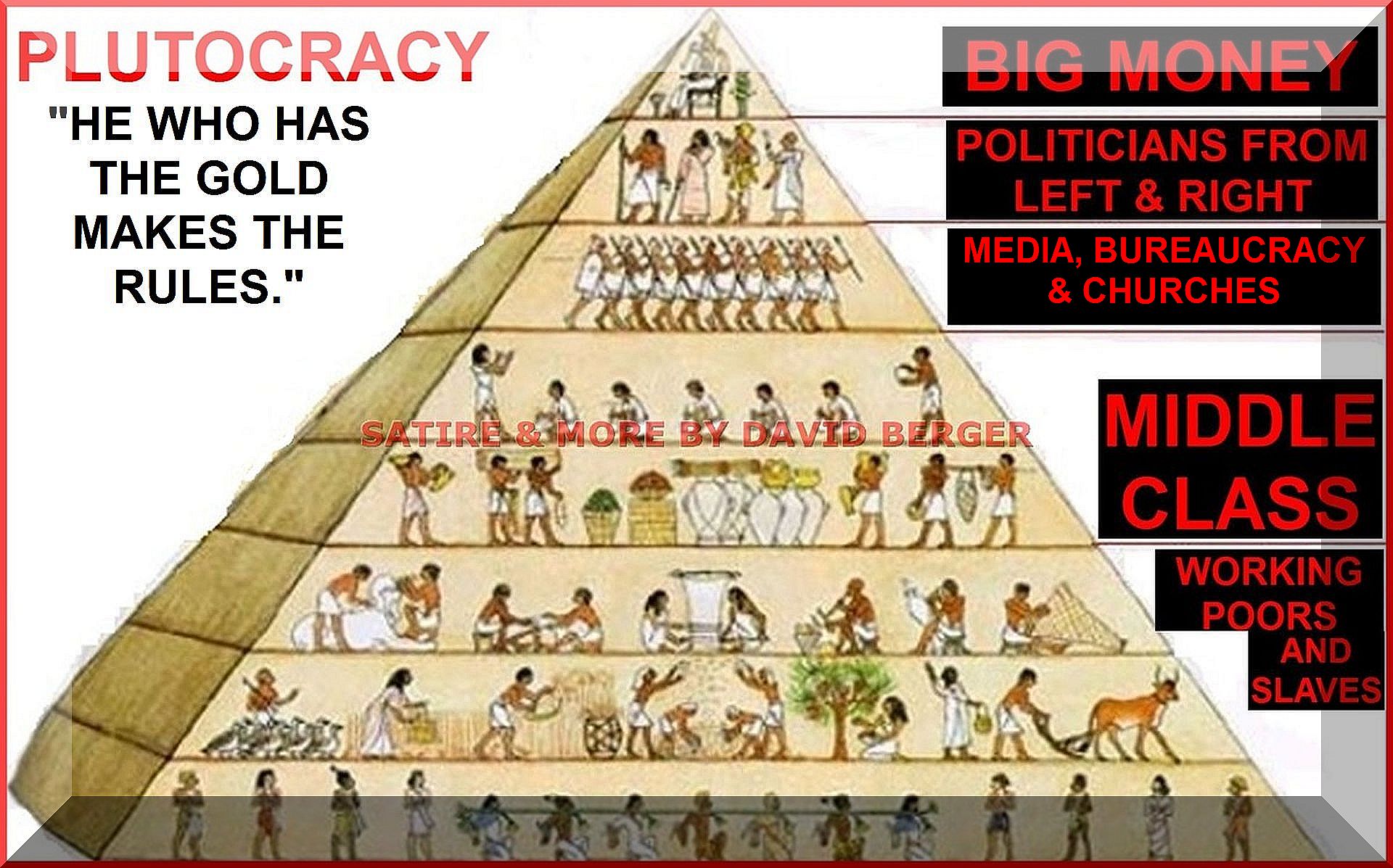

Liberals and Socialists

Philosophers of liberalism and socialism actually have very different visions for the world. They don’t disagree at all on the idea that spreading the wealth around is good for everybody. In fact, this idea finds one of its greatest expressions in the work of the philosopher of welfare liberalism, John Rawls. He proposed…